At the Bucharest airport lobby a half-dozen patient Romanians had waited hours to haul our American asses to their mountains.

We were there as a delegation of Appalachian scholars to a conference with our Carpathian counterparts.

University student Bogdan Petrescu wildly drove us in a near-pristine Volkswagen coupe from Bucharest to Brasov. It was a luxury car, which made him insecure.

“It’s my father’s,” he sheepishly said.

He drove it like a frenzied fish.

“Do you like The Script,” he asked before playing their latest.

“Do you like Gotham?” he continued.

I never expected to be talking about Family Guy with the first Romanian I’d met, but I also had no idea how much love Romanians felt toward American culture.

He has pointy, full eyebrows, sandy hair, and striking round eyes with pursed lips. He is handsome, but probably has no idea he’s the Romanian Brad Pitt. Or, at least, he failed to act like it.

His excitement toward our culture, particularly his love of DC superheroes, gave us the first hint of America’s importance in Romania. From MTV to Hotel Transylvania 2, American entertainment had landed in the Carpathians. At first I was embarrassed by his love for my vapid culture, but throughout my stay the familiar, even Minions, made me homesick.

I am envious of the Romanian accent. It has the stop and start flow of Russian with the rolling wave of the romances; like Italian with a touch of Khuzdul. The etymology of the language is mostly Latin with a dash of German, hinting at eras of oppression. Knowing Italian or Spanish helps, but Romanian is unique.

“This is the smell of Ploiesti,” Bogdan explained.

Petrol refineries assaulted the air with the distinct odor of carbon monoxide as we raced past the largest toy store I’d ever seen. In the States, most pollution is scentless, invisible. Here it’s poisonous. My body immediately began to respond, subtly and searingly.

The fumes circulated and exited through the A/C as the light from neon Coca-Cola signs permeated the vehicle with reddish hues, unveiling the blurred profiles of my companions.

I was far too wrapped up in my American-ness and the constant challenge of the “association game.” Carrefour is the Romanian Wal-Mart? It’s embarrassing, I know. I simply could not help myself. I commented on how relatively cheap goods were and began many phrases with “In the states…” I failed my new friends, I fear, by judging their country according to the ridiculous standards of mine.

The bird shit-covered produce at the market boggled me.

“If the water is unsafe to drink,” I asked Bogdan, “then what do you wash the fruit with?”

“Water,” he replied, without a trace of irony.

Romanians must learn English in kindergarten. By high school most are fluent in 3 or 4 tongues. Like most of his countrymen, Bogdan’s English was good, but not quite excellent. After decades of immersion in the ballad of Tommy, Gina, the docks, and a penchant for conversing with God, Iuliana, Bogdan’s girlfriend, spoke near-perfect English, thanks to her father’s passion for Bon Jovi.

Still, they were not blindly enamored with the “great American visitors.” They maintained a curious boldness and skepticism that led to questions deeper than most Americans ask about themselves. Like, “why is our banking system so predatory?” They could not fathom why going into debt is the only real currency. And, as a horrible American, I could not justify the tradition.

Why does an explanation about absurd American policies and practices typically begin or end with, “well, a company wanted______?” They wanted explanations; I felt like I was trying to paint water.

Ultimately, these Romanians seemed more concerned with their own reality than that of others, a practice in which maybe we all should participate.

Romanians mark their past as before or after their revolution against communists. We simply have no modern equivalent for that in America. The closest are 9/11, or maybe now, the COVID-19 pandemic.

On December 13, 1989, Brasovian citizens revolted against the Romanian communist regime.

Their bullets sliced through buildings and bodies and ended decades of totalitarian rule. My Romanian friends are from the first post-revolution generation. I tried to wrap my head around the reality of living in a nation so soon liberated.

They struggled to understand what standing in line for bread felt like for their parents. Pushed and pulled, they must somehow balance opportunities not available to their parents in a time when celebration is also important. To them, McDonalds and higher education are inalienable rights.

Not all Romanians feel comfortable in the Republic. Social mobility arrived but is unfair, falling under economic and class pressures. Political power is often obtained through corruption and politicians work to serve their own needs first. Some miss the unity between Romanians. (They may have suffered, but they did so together.) Family traditions crumble as the young move to seek continental opportunities. Some older Romanians wonder whether communism was so bad after all.

Bullet holes from the revolution pepper building façades. Sections are set aside within frames in memoriam. Decades of untouched grime highlight the macabre relics of destruction like a photo, or time capsule. The nation is moving forward, but they are keenly aware of the risk of forgetting their past. This keeps Romania suspended between tradition and progress, the old and the new.

Photo Courtesy Anthony Sadler

It also teases why the Carpathians are so unlike the Appalachians; there is an element of choice in their culture, especially in what they retain. Just because they have some of the fastest Wi-Fi in the world does not mean they had to forfeit their heritage.

In the remote village of Magura horses drag wooden wagons with car axles while juveniles follow on dirt bikes. They embrace tourism and running small inns, bread and breakfast style, called pensions, while others stack hay using traditional methods and tools. Traditional wooden homes with beautiful and ornate external carvings uphold TV satellites that beam The Nanny into their living rooms. At la Ciocolata, a shack, a family serves Romanian plum moonshine called tuica (pronounced ts-weeka, with a tsunami-styled tis!) from recycled Fanta bottles aside Coke and chips. Is this a transition or equilibrium?

I have a fantasy of returning to Romania seeking signs of change. After all, entire cultures have disappeared under the guise of progress. Identity gets lost in modernity. The beastly mainstream sweeps it away, unromantically, into the arms of normalcy.

Will Romania end up like us? I don’t know, but I sure hope not.

I thought I came to witness people struggling on the land, working harder than deserved, like Adam and Eve after the fall: exiled from Eden. In short, people who needed us to tell them how to live, or at least think.

Instead, I was enlightened. I discovered a horribly kept secret: The United States of America is not the best model for freedom. Romanians prove that we are wrong and right. We were right to take matters into our own hands against the British Empire, but we are wrong to think we own the franchise.

There is an army waiting to guard the Romanians against this fate. Some are more determined than others, but the message is clear; protect what is left of what makes you “strange.” Coming from Appalachia, the Carpathians should heed that advice.

The mountain cultures of the eastern United States long ago fell to the call of capitalist prosperity. Cultures bled out and formed puddles of homogeneity. Industrialists raped, reaped, and rendered the mountains remains. Its people were set aside, for entertainment purposes only.

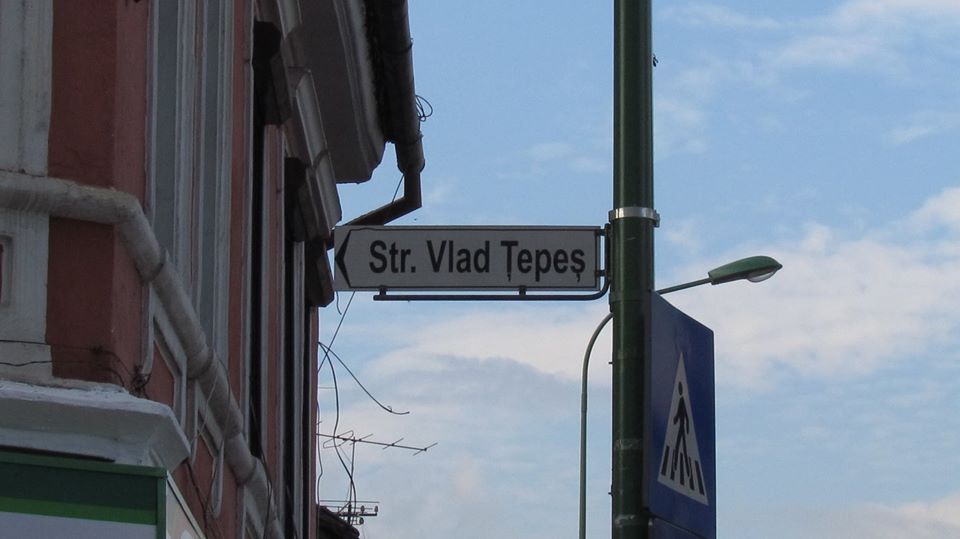

Dracula is a Carpathian mountain stereotype. Romanians resent this like Appalachians detest the “hillbilly.” They defend the honor of Vlad Tepes more than 500 years after he impaled thousands of his enemies in Transilvania. (Damn that Irish Stoker and his cultural appropriation.) Still, they sell kitschy baubles like Dracula snow globes or Cabernet Sauvignon bearing the famous likeness of ‘Vlad the Impaler’ to pay the bills.

Photo Courtesy Anthony Sadler

I went to Castle Bran, the backdrop for Stoker’s horror masterpiece, where Vlad never slept. Our Romanian friends apologized for its disingenuousness. Surrounded by what looks like a southern flea market, the Castle had an entire room dedicated to the Dracula story. It is a place that knows its place in the Romanian saga and peasants are more than capable of capitalizing on those blurred historical lines. Apparently, my new apologetic friends had never seen Dollywood.

Romania and I had a weeklong affair that bordered on the shallow but teetered into lifelong. It was a rocky start. I came for the stereotypes: espresso, pastries, peasants.

It was like starting in the middle of a great book. I tried, but probably failed, to grasp the context. I left just when it got interesting. Its claws dug into my side and left a mark. Bogdan, Iuliana, Magura, and my new stateside friends created a fresh world for me that was bound by time and experience–temporary yet meaningful. They, and Romania, seem fictional to me now, precisely because of how fantastic they are.

These thoughts, and this whole experience, are selfish. Could it have been any other way? Is a truly foreign experience possible?

From the moment I landed in Romania I knew my time was limited. I took from that place and those people a sense of a better life. I gained so much that I will probably never fully comprehend. My only real hope is that, in return, the theft was not so apparent. I also hope I left a sliver of myself somewhere along those ancient streets, in the piazzas, or haphazardly dancing on the uneven steps of the Rasnov citadel. Like a t-shirt purposely left after a tryst, I hope to return some day and retrieve what’s mine.