Image Courtesy of Hargrett Library

Monday, May 25, 1840–

The turbid waters of the Oconee swelled. The artery of a nascent Athens community revolted. The rains began that afternoon and created an injurious effect: the Greatest Natural Disaster in Athens’s History.

For days it rained relentlessly. Banks gave way in the Oconee and Savannah watersheds. Milledgeville (then the state capital), Augusta, and Savannah had their livelihoods taken by the caramel waters that fueled their economies.

There was a spring just northeast of Old College, now long-drained, that once served the entire community. When the freshet came, it spilled out onto North Campus and rushed down College and Broad (then called Front Street.) The town was flooded and Athens, small but burgeoning, received a deleterious blow.

In 1840, Athens was a hamlet born from the University of Georgia. The Oconee was the heart of the economy.

North of Hancock, the forest dominated. A mile east of the Oconee was the eastern city limit, the Cobbham district the western. Old College was the southernmost building of any consequence to the south. Only those who lived in what is downtown today called themselves Athenians.

Athenians enjoyed their seclusion. Outside news did not arrive for weeks. They had the university for entertainment, cultural enrichment, and to keep the town stocked with educated citizens. In this era, lawyers, doctors, and other educated tradesmen began to graduate and stay in the Classic City, raising the prominence and promise of its future. Still, more than eighty percent of Athenians were farmers. Small cotton, tobacco, and food crops sustained the township. Just outside the city, down the roads to Lexington and Augusta, out toward Oconee county, and north toward Commerce, cotton and slavery were ubiquitous.

The names of the era’s most prominent men–Clayton, Hancock, Cobb–became the names of Athenian streets and buildings. This was the era when Athens became a manufacturing city.

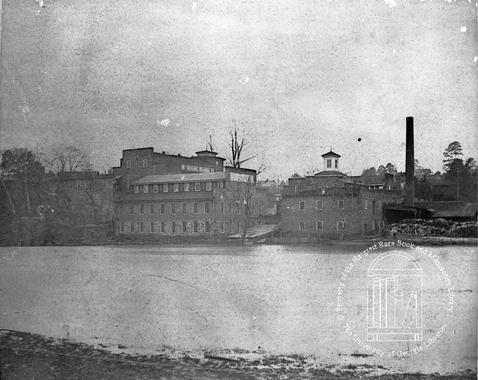

Those men grew tired of paying high tariffs for manufactured goods. The roads out of the city were knee-deep in mud, which stripped the flesh from horses. They pooled their funds and opened a cotton manufacturing plant, the Athens Manufacturing Company, in 1833. By 1840, Athens boasted four factories on the Oconee. Also in the 1830s, the Georgia Railroad Depot opened its first lines in Athens, where the Multi-Modal station sits today.

The Athens Manufacturing Company employed ten percent of the population.

Photo Courtesy of Hargrett Library

The Harrison Freshet tore it to pieces that floated down the angry river. The freshet disrupted rail lines. Houses, stores, and mills crumbled and meandered the swollen fluvium. Entire plantations were lost. Stories surfaced about hundreds of bales of snow-white cotton–which might as well have been gold–floating hopelessly down the Oconee. Athens had two bridges, both lost during the flood. No bridge stood in Clarke County by the third day of the rains. The city that preferred seclusion was effectively cut off from the rest of the world.

In time, the city rebuilt buildings, bridges, and boulevards. They came back stronger and larger than before. More railway depots opened. It took the community to rebuild, working together, and investing in one another.

In time, the city grew more prominent, further separating their endeavors from the university which provided its foundation. Many businesses opened in the years preceding the Civil War. Athens grew exponentially.

All rivers in Antebellum Piedmont were moody. They were filled with eroded soils from overworked cotton and tobacco lands. Twisted and tortured by dams, locks, levees, and canals. When spring rains came and winter snow melted, natural and necessary freshets–once used by natives to replenish floodplain soils–became disastrous. With Athenian help, the Oconee River was a malevolent maelstrom.

The city learned to move its heart–its livelihood–away from the intemperate river.

Today, the river flows almost without notice throughout our great city and we lost the connection we once had to it. We damage it daily in ignorance. Its caramel broodiness sometimes spills over into our backyards, backs up into streets, or simply gives us alarm after days of non-stop rain. Alas, upper watershed dams keep the Oconee at bay. The once wild river, which helped cut the hills that dominate our view and torture our runners, is now a bubbling brook that provides summer passage for the tubes, kayaks, and Terrapin-filled coolers of modern Athenians.

We live in a city determined to thrive, sometimes at the expense of our history. Ruins of tracks, factories, and stores stand guard over us like skeletons, reminders of our heritage. Countless others were demolished to make room for new ideas, to replace the slagging hopes and dreams of our ancestors with promises of prosperity.

The process seems never-ending.

Original Article Published on Source Athens.